Introduction

Thoracoscopy plays a growing and increasingly significant role in our daily practice, now ranking as an essential technique in diagnosis and treatment of respiratory disease1–3. While in most cases thoracoscopy is performed by surgeons under general anesthesia, it can also be performed by internists when restricted to pleural lesions. For example, pleural effusion aspiration is generally performed for evaluation of pleural effusion pooling to obtain a diagnosis based on cytological, microbiological, and biochemical analysis, while blind pleural aspiration is performed to obtain pathological diagnosis. In many clinical cases, these examinations can provide a definitive diagnosis. However, in a nontrivial number of cases, obtaining a diagnosis may prove difficult. Should this occur, the rate of correct diagnoses can be improved significantly by using direct observation inside the thoracic cavity to confirm and biopsy the lesion.

Almost three decades have already passed since we first introduced thoracoscopy under local anesthesia in 1993. During that time, we have performed the technique on innumerable cases and reported on the efficacy of the procedure. While the technique has been widely disseminated, even today many facilities have yet to take advantage of this powerful therapeutic procedure.

In this booklet, we hope to make it easier for facilities to introduce thoracoscopy under local anesthesia by offering a general overview of the procedure and a more detailed look at some of its specific techniques.

Indications

■ Target diseases and efficacy

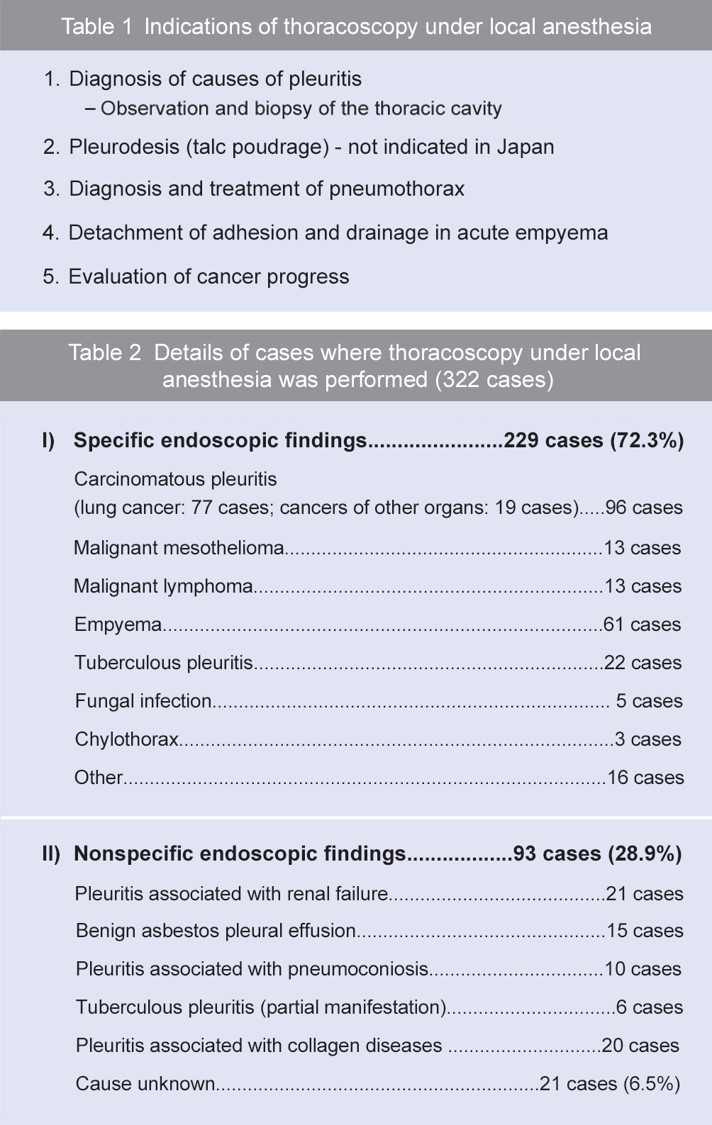

The main purpose of thoracoscopy under local anesthesia is to obtain a definitive diagnosis of pleural effusion cases by performing direct observation and biopsy inside the thoracic cavity (Table 1).

In the respiratory department, thoracoscopy under local anesthesia is usually applied not only to cases where a pleural effusion examination and needle aspiration have not produced a definitive diagnosis, but also in cases where pleural effusion drainage is necessary. The primary purpose of this procedure is to detect carcinomatous pleuritis, malignant mesothelioma, and tuberculous pleuritis. These three diseases are the ones that benefit the most from thoracoscopy since biopsies are critical to their diagnosis and they require early diagnosis and treatment.

As for pneumothorax, it is possible to treat the bullae by looping them or coagulating with an electrosurgical device under local anesthesia. However, the thoracoscope cannot reach lesions located in blind spots such as on the apex or on the mediastinal side. Treatment of pneumothorax is not generally performed with thoracoscopy due to the difficulty in confirming leaks. However, it can make it easier to establish a treatment policy – whether to perform a surgical intervention or conservative follow-up – when the pleural cavity has been observed during drainage to check the locations and degrees of the bullae.

With acute empyema, compartments tend to form rapidly due to fibrin deposition, which often makes it difficult to perform drainage. In this case, thoracoscopy can be used to detach the adhesion and accomplish effective drainage – especially when performed at as early a stage as possible.

Likewise, pleurodesis using talc is now performed for the purpose of controlling pleural effusion caused by carcinomatous pleuritis – particularly in Europe and North America – and favorable results have been reported4. This procedure is not covered by health insurance coverage in Japan, but we have found it highly effective especially when talc is sprayed by means of thoracoscopic talc poudrage (TTP)5. Table 2 shows the details of thoracoscopy under local anesthesia that we have performed.

■ Respiratory functions

Although it is difficult to summarize the respiratory functions and physical status required for thoracoscopy under local anesthesia, it can be considered feasible if the patient is able to undergo ordinary bronchoscopy. Before performing thoracoscopy, the patient’s physical status based on the results of chest X-ray, chest CT, arterial blood gas analysis, and electrocardiography should be taken into account.

■ Pleural effusion

Aspiration of pleural effusion is easier when the fluid is pooled to some extent. However, when excessive pooling has led to severe lung collapse, re-expansion pulmonary edema (RPE) may occur after the drainage of pleural effusion. Consequently, it is recommended that as much fluid as possible be drained until the day before the examination. If there is no pleural effusion, such as when a chest tumor is present, an artificial pneumothorax should be created before thoracoscopy. In some cases adhesion causes pleural effusion to be present only locally. Therefore, preprocedural confirmation with ultrasonography is always required.

■ Contraindications

Since one of the lungs is collapsed during this procedure, it is difficult to perform on a patient with severe respiratory dysfunction or hypoxemia. As is the case with general surgical procedures, it is important to ascertain whether the patient has ischemic heart disease and arrhythmia. In addition, cases suspected to have hemorrhagic diathesis, severe adhesions, and extensive adhesions could also be contraindications.

- Content Type